Pain Doesn't Create Motion. Constraints Do.

Marcus Cauchi dropped a sharp take recently that's worth sitting with:

"Discovery isn't about finding pain. Pain is already there. If pain created change, buyers wouldn't need you. They would've changed before you arrived."

He's poking at something real. The distinction he's drawing—between pain as feeling and constraints as facts—explains a pattern every experienced seller has seen: calls that feel productive, discovery notes that look thorough, and deals that still stall.

The usual diagnosis is that you didn't find enough pain, or the pain wasn't urgent enough, or you failed to "amplify" it properly. Cauchi is saying something different. He's saying pain was never the mechanism. Constraints are.

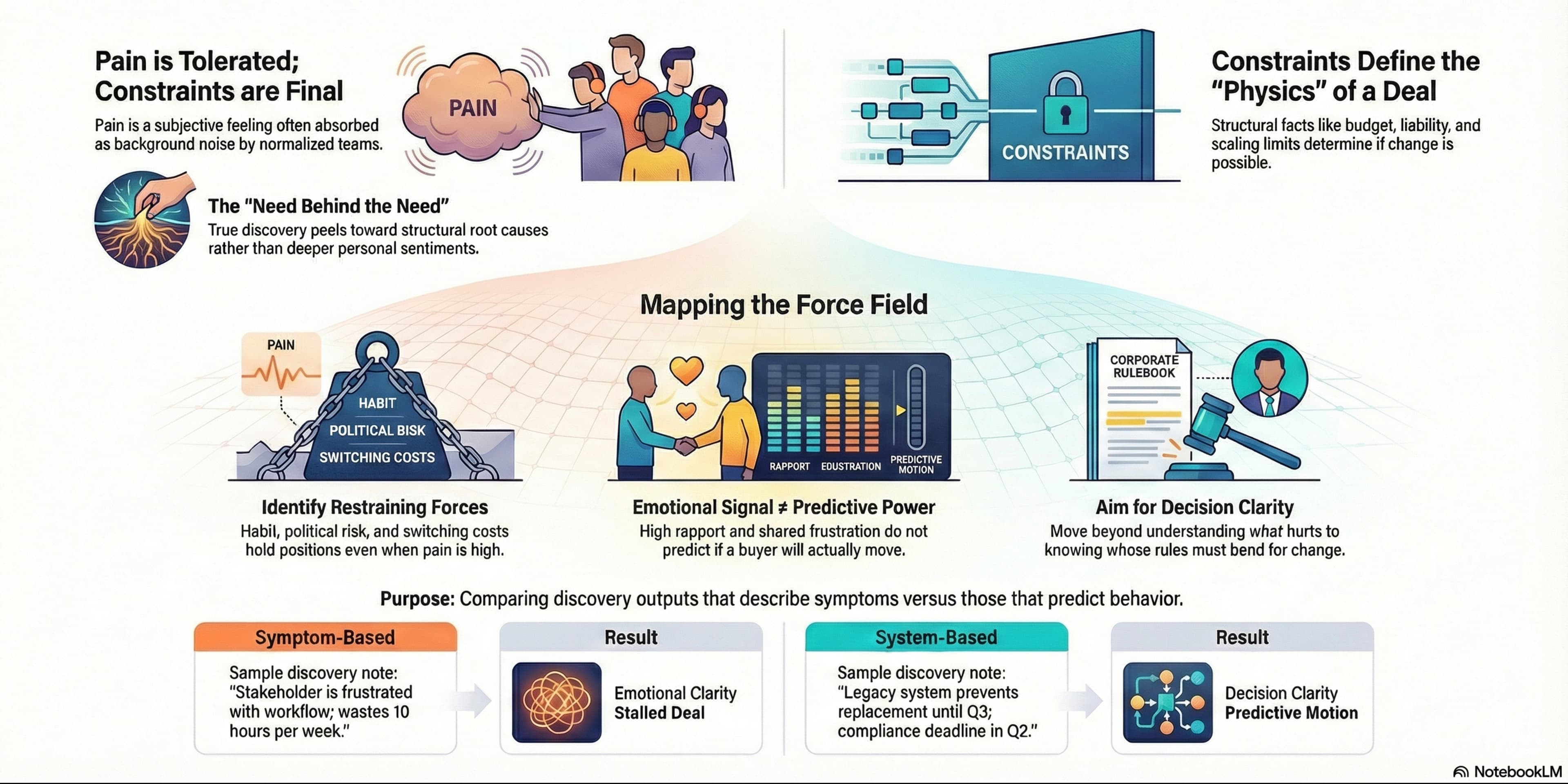

Pain Is Tolerated. Constraint Failure Is Not.

Organizations live with pain for years. Inefficient workflows. Frustrated teams. Obvious problems everyone acknowledges. The pain is real. It's also absorbed. Teams normalize it. Leaders deprioritize it. The pain becomes background noise—present but not actionable.

What organizations cannot live with is a broken constraint. A budget ceiling that forces a choice. A compliance exposure that creates liability. A missed board commitment that threatens credibility. A system that literally cannot scale to next quarter's demand. A key person quit because the pain finally exceeded their tolerance.

Pain is subjective. It can be softened, rationalized, or endured. Constraints are structural. They define what can and cannot continue. When a constraint breaks, the system has to respond. That's when change becomes possible.

The implication for discovery is uncomfortable: most of the emotional signal you're collecting doesn't predict motion. It predicts rapport.

The Force Field Nobody Teaches

What Cauchi is describing—without naming it—is Kurt Lewin's force field analysis. Lewin was a psychologist who studied how change actually happens in organizations. His model is simple: any situation is held in place by two sets of forces. Driving forces push toward change. Restraining forces hold position.

The key insight is that change doesn't happen by intensifying the push. It occurs when the restraints weaken.

Pain is a driving force. It creates pressure toward change. But pressure alone doesn't move anything if the restraints are solid. Budget limits, approval structures, competing priorities, political risk, habit, switching costs—these are the restraining forces. They don't care how much pain exists. They hold their position until something breaks them.

Most discovery conversations overweight the push and ignore the hold. Sellers surface frustration, get nodding agreement, and write detailed notes about challenges. But they never map the restraining forces. They never ask what they would have to give. So they leave with emotional clarity—a clear picture of discomfort—but not decision clarity. They can't predict whether anything will actually move.

This is why Cauchi distinguishes between running a discovery and running an interview. An interview collects stories. Discovery maps the physics.

The Need Behind the Need

Chris Orlob has a line that's become gospel in sales: buyers never reveal the real problem after the first or second question. Uncovering the "need behind the need" is the closest thing to a magic bullet.

He's right about the method—keep peeling. But most sellers peel in the wrong direction. They hear "need behind the need" and drill toward deeper emotion. "What keeps you up at night?" "How does this impact you personally?" Each layer reveals more feeling, but no more physics.

Compare that to Orlob's actual question: "What's going on in the business that's driving this to be a priority?"

That's not asking how someone feels. It's asking what structural pressure made this matter now. What changed. What broke. What can no longer continue. That's a constraint question dressed as empathy.

Orlob puts it directly: "Products don't solve problems. They address root causes." Root causes are structural. They're not "we're frustrated"—they're "our systems don't talk to each other," or "the team that owns this has different incentives," or "we don't have visibility until it's too late."

The need behind the need is usually a constraint, not a feeling. Peel toward structure, not sentiment. Same technique. Different target. Completely different output.

Where Pain Fits

This doesn't mean pain is irrelevant. Pain matters, but not as a headline. Pain tells you where attention exists. It shows you what the organization is aware of and willing to discuss. That's valuable. Awareness is a precondition for change.

But attention isn't energy. Energy for change comes from constraint pressure—the thing that cannot continue. A team can be frustrated forever. A team can't miss quarterly numbers forever. The constraint creates the energy. Pain just makes it legible.

In Jobs to Be Done terms, pain sits in the "push of the situation" quadrant—the dissatisfaction with how things currently work. But the forces model includes three other quadrants: the pull of the new solution, the anxiety of switching, and the habit of the present. Constraints live in that second pair. They're the forces that hold position even when pain is high.

JTBD practitioners who use the full forces model already know this. The ones who reduce JTBD to "find the pain point" get the same results as traditional discovery—emotional signal without predictive power.

The Question Behind the Question

Here's where this gets interesting for the work I've been doing on coordination and power.

Constraints don't appear from nowhere. Someone set the budget ceiling. Someone defined what counts as acceptable risk. Someone determined which initiatives get resources and which get deprioritized. These aren't neutral facts about the organization. They're crystallized power. They're the residue of past decisions about who gets to say what matters.

When Cauchi says real discovery exposes "decision mechanics," he's pointing at the org chart that actually governs behavior—not the formal hierarchy, but the structure of constraints that shapes what's possible. Mapping constraints is political cartography.

This means the question "what would have to give for this to change" is really asking "whose rules would have to bend." That's a different kind of question than "how frustrated are you with the current situation?" It requires understanding how the organization actually works, who has authority over the relevant constraints, and what would create permission for those constraints to shift.

Most sellers don't ask these questions because they feel awkward or presumptuous. But they're the only questions that predict motion. Everything else is atmosphere.

The Practical Shift

The shift Cauchi is advocating—and I think he's right—is from symptom collection to system physics.

Instead of "tell me about your challenges," the question becomes "what happens if this doesn't change?" Instead of "how long has this been an issue," the question becomes "what would have to be true for this to get solved?" Instead of "what's the impact on your team," the question becomes "what breaks if this continues?"

These questions aren't harder to ask. They're just aimed differently. They're not trying to surface feelings. They're trying to locate the structural conditions that govern change.

The result is a different kind of discovery note. Not "stakeholder expressed frustration with current workflow, estimates 10 hours/week wasted." Instead: "Current workflow constrained by legacy system that can't be replaced until Q3 due to integration dependencies. Compliance review in Q2 creates a hard deadline for documentation improvements. Budget authority sits with VP Ops, who is measured on cost reduction, not efficiency gains."

The first note describes pain. The second note predicts behavior.

The Diagnostic

Cauchi offers a clean test: if your calls feel productive but decisions keep slipping, you're not missing pain. You're missing decision mechanics.

You've created emotional clarity. The buyer leaves understanding that something hurts. But you haven't created decision clarity. They don't leave knowing why nothing moves or what would have to change for movement to become possible.

Pain without constraint mapping is just storytelling. The stories might be true. They might be detailed. They might generate rapport and trust. But they won't generate motion—because motion doesn't come from feeling. It comes from structural pressure that can no longer be absorbed.

The job of discovery isn't to expose discomfort. It's to reveal what can't continue—and what has to give when it can't.

This is a working piece toward V3 of Distribution Is Hard. The constraint/coordination framework is becoming central to how I think about why good products don't spread and why obvious changes don't happen. More on this soon.

Pain Doesn't Create Motion. Constraints Do. Most discovery advice: find the pain, amplify the pain. Problem: Organizations live with pain for years. What they can't live with is a broken constraint. Wrote about the difference—and why it changes what questions you ask. Post + audio breakdown below.

Right sir 👍