Is There Objectively Good Writing?

On finding the beauty in what's already there

An all-too common position today when it comes to the arts (and creative work in general) is that quality is subjective. The individual consumer’s perception is paramount, and all attempts at subjecting art1 to criteria of quality feel wrong, somehow, mostly because nobody can agree on what those criteria should be in the first place; and because art is always changing.

I was inspired to write this essay after reading Clancy Steadwell’s note below. I’m not sure if he’s entirely serious here (or if he 100% believes in this position), but it serves as a good jumping-off point to discuss subjectivity-objectivity in creative output.

The Case for Subjectivity

The art is subjective is a common contemporary idea, but it’s worth noting that in the history of art and criticism, it’s a fairly new one. For most of Western history, art criticism operated on the assumption that artistic quality could be measured against standards that transcended individual taste. The ancient and medieval idea held that beauty was essentially objective. Critics focused on qualities like proportion, harmony, symmetry, and order to measure and define these qualities; they were less interested in an individual perceiver’s response to a work of art.

In the first work of artistic criticism, Poetics, Aristotle examined the structural elements of tragedy, identifying what made some tragedies better than others. He identified the key elements of the form: unity of action, proper magnitude, catharsis—and compiled a a structure in which to judge tragedies against these qualities. For Aristotle, Oedipus Rex is a success because of its strengths in these key elements, not because he (or the Athenian audience) personally enjoyed it (though they also did)2.

Medieval aesthetics took Aristotle’s ideas and folded them into their theological understanding of the world. Beauty was a transcendental property, a reflection of divine order. Cathedrals weren’t beautiful because people liked them; they were beautiful because they reflected medieval metaphysical ideas about cosmic harmony3.

The link between aesthetics and objective standards began to break down in the eighteenth century. David Hume explored the tension between objective and subjective creative standards in Of the Standard of Taste. Hume acknowledged the obvious variation in taste but refused to conclude that “all sentiments are right.” Instead, he put forward the “true critic” whose delicacy of imagination, sensitivity, freedom from prejudice, and other exemplary qualities offered weight to their aesthetic judgments.

Immanuel Kant had a similar, if slightly more subtle, idea. In Critique of Judgment, he laid out the argument that aesthetic judgments are subjective; they are grounded in feelings, not concepts. However, Kant complicated this assertion by also arguing that aesthetic judgments claim “universal validity.” What that means is that when I say, “this is beautiful” about something, I’m both reporting my individual (subjective) pleasure and making an implicit claim that you (and others) ought to agree, even if I can’t prove it through any formal argumentation. For Kant, beauty involves a free play between imagination and understanding; it’s an emergent quality of different minds sharing ideas.

Both Hume and Kant helped push aesthetics out of the realm of objectivity and towards notions of intersubjectivity (notions of beauty as shared quality, filtered through either “true critics” or implicit judgments between multiple people). But the Romantics pushed the idea further, all the way to aesthetic subjectivity. They focused on individual genius and emotional authenticity, putting the individual artist’s vision at the center. External standards were seen as secondary, even oppressive. For the Romantic, the artist is free to create (and express themselves) and cannot and should not conform to objective standards.

Then the twentieth century broke art into a million pieces, both entrenching the Romantic idea of subjectivity and rendering critical judgments extremely difficult, even incoherent. Modern art movements emphasized the pluralism of expression (a lovely outcome of Romantic ideas of personal artistic vision, but a nightmare for critical judgment). How do you apply the same aesthetic criteria to Schoenberg and Stravinsky, Joyce and Hemingway, Mondrian and Dalí?

So beleaguered by the variety of artistic output, some critics (like Morris Weitz) effectively threw up their hands and declared art undefinable4. Marcel Duchamp put the nail in the coffin by challenging many of the key assumptions of what art even is. Postmodern and poststructural criticism continued this assault, challenging all ideas of stable meaning, even authorial intent.

The Romantic notion of personal genius, underpinned by Kantian ideas (aesthetic judgments are feeling judgments), and filtered through the diversity of artistic movements in the last century, combine to form our contemporary understanding that aesthetics is fundamentally subjective. It permeates all creative work today.

If art were truly subjective, then criticism would be useless; worse than useless, it would be a lie. And many people feel this way, who hold their own opinion paramount, unassailable (and certainly not subject to the opinions of a bunch of stuffy critics). Yet, criticism remains, hobbled though it may be. Our age has no shortage of strong, serious critics, and even if those critics are reluctant to articulate universal standards, they must operate with implicit ones. When a critic argues that a novel has failed, they’re not just reporting personal displeasure; they are also making claims about craft, coherence, originality, depth, and so on, ideas they expect their readers to recognize.

Despite this Romantic, lay understanding of art as personal expression, canons, consensus, and criticism continue, suggesting that perhaps we don’t really believe that art is completely subjective, even if, as Kant identified, we struggle to articulate how it could be otherwise.

The Case for Intersubjectivity

While the layperson can hold the idea that art is subjective, the critic must hold (at a minimum) the idea that art is intersubjective. Else their entire project is a waste of time. What is intersubjectivity? It’s a sort of compromise between the two poles of subjectivity and objectivity. If something is subjective, it exists only in your mind (feelings, qualia, etc.) and cannot be accessed or verified by someone else. If something is objective, it exists outside of you (the moon, Venus, a particular tree) and can be verified by other people. For something to be objective, it must also, crucially, exist even if there are no other minds to verify it. If all life on Earth goes extinct, the moon will continue to exist.

Intersubjectivity is an interesting blend of the two. If something is intersubjective, it does not exist in one mind but in multiple minds. It is a shared understanding, meaning, or experience between two or more people. Cultural norms and understandings are intersubjective. Money is also intersubjective; so are nations and borders. The five-dollar bill in my pocket has no objective value as paper, but represents a level of purchasing power within our shared (intersubjective) economic system. If all life on Earth goes extinct, the value of the US dollar ceases to exist, but the moon persists. When I die, all my subjective ideas (my feelings, memories, qualia) will cease to exist, but the idea of the US dollar will persist. Intersubjective things exist only because we collectively agree to treat them as though they exist.

Does that not sound like art? A work of art is beautiful because a group of minds agrees that it is so (Kant’s idea of free play between minds). Writers are “in dialogue” with each other through time; they are influenced by each other, and influence each other in turn. We can identify beauty through this intersubjective lens of influence. What do all these writers have in common: Agatha Christie, William Faulkner, David Foster Wallace, Iris Murdoch, Ray Bradbury, Ngaio Marsh, Robert Frost, Aldous Huxley, Margaret Atwood, Paula Vogel, Edith Wharton, Angela Carter, John Steinbeck, Tom Stoppard, Philip K. Dick, Chang-rae Lee, Jasper Fforde, Allistair MacLean, John Green, and Gabrielle Zevin? They all have titles or plots pulled directly from lines in William Shakespeare’s work5. And that’s just the titles; let alone how Shakespeare influenced word choice, rhythm, themes, characters, metaphors, and so on. These works form a visible network of influence, with Shakespeare as a central node that connects writers across centuries, cultures, and genres, signaling a grand participation in a shared literary conversation.

You could theoretically map this web of intersubjective influence. I imagine it would look similar to “domain authority,” a way to rank different websites and their clout with search engines. Domain authority measures a site’s search ranking potential by analyzing its backlinks (what other sites link to it), assessing not only quantity but also the quality of sites (a link from WebMD carries a lot more weight than a link from a doctor’s personal blog). In this literary version, references from highly-referenced writers would “mean more” in the intersubjective rankings.

This hypothetical system is essentially what criticism seeks to do. It tracks (and reveals) the web of artistic influence. Influence is both conscious (writers will often cite their predecessors) and unconscious (it seeps in from the cultural context in which the writer lived). The critic’s role is to map this web of influence, especially the unconscious connections.

Compare, for example, the opening of Shirley Jackson’s novel The Haunting of Hill House with an earlier predecessor. Here’s how Jackson began her novel:

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream.

Hill house, not sane, stood by itself against the hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

Now, take a look at how H.P. Lovecraft began his story “The Call of Cthulhu”:

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piercing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

Do you see how these works echo each other? Jackson was clearly inspired by Lovecraft’s story, such that when she set down the opening to her novel, she positioned her work in direct relation to his story. But Jackson doesn’t just echo Lovecraft’s ideas; she enhances them. While Lovecraft described madness in terms of cosmic vastness (the sheer size of the universe, the incomprehensibility of deep time), Jackson put that universal unknowingness directly in the home. What if your house were mad? If you’re interested in this specific comparison between Lovecraft and Jackson, I wrote a long piece about this horror convention, including Thomas Ligotti’s place in the evolution of this idea:

Enter the Dollhouse—The Stories of Thomas Ligotti

·

May 22, 2024

Many readers are turned off by literary criticism, finding it confusing and esoteric. This is unfortunate, because criticism is highly valuable to readers, providing a map of influences that can guide your reading. Without good criticism, we are stuck with genres as the predominant “reading map,” which do more to trap readers in a cul-de-sac of repeated concepts than progress them through a deeper understanding of the evolution of ideas.

Despite all the jargon, literary criticism is actually quite simple and easy to explore: just read backwards, following a trail of influence. You will see the intersubjective landscape much more clearly (when critics talk about “postmodernism” and “autofiction” and “new sincerity” and all these terms, what they are really describing are specific nodes in the intersubjective web of influences); you can dispense with all the terminology and simply explore the web on your own. If you like Carmen Maria Machado, read Shirley Jackson; if you like Jackson, read Lovecraft; if you like Lovecraft, read Arthur Machen, and so on. Instead of getting stuck in genres or reading “the canon” in order, starting with the Greeks and frog-marching your way through time, go backwards instead; identify the authors you love and read backwards through their influences. As you go, you will discover new bunny trails, authors that are related in ways you didn’t expect. And if you can illuminate these paths for others, then you are performing literary criticism—a good and useful service.

Lay readers think that art is subjective because they are blind to this intersubjective web; they literally cannot see it, both because they have not read systematically and because critics have failed them.

An excellent overview of this intersubjective web of literary influence is Lincoln Michel’s essay, “The Grand Ballroom Theory of Literature:

The Grand Ballroom Theory of Literature

5 months ago · 150 likes · 24 comments · Lincoln Michel

The Case for Objectivity

But what if art isn’t merely intersubjective? What if some creators, as if touched by strange gods, have managed to illuminate something deeper, something fundamental about the nature of reality? What if art can reveal the True and the Eternal? What would that mean for creativity? For writing?

It’s a strange idea, and an unfashionable one. As I’ve argued in this essay, the notion of objective artistic standards has fallen out of our cultural understanding. If anything, art is most likely intersubjective; neither completely subjective nor completely objective.

But in his book The Beginning of Infinity, the physicist David Deutsch lays out a fascinating argument for the existence of objective beauty. He expounds on his argument in a lecture for the Irish Museum of Modern Art, “Why Are Flowers Beautiful?” which is available here:

You should watch the video—it’s extremely interesting. But I’ll also summarize Deutsch’s argument here.

Flowers evolved to attract insect pollinators, not humans. Yet humans find flowers beautiful, too. This is a puzzle if beauty is purely subjective or culturally constructed (i.e., intersubjective). Why would our aesthetic responses align with those of insects, whose organic machinery is different from ours on orders of magnitude, separated by hundreds of millions of years of evolution?

Furthermore, plants, too, are separated from insect pollinators by hundreds of millions of years of evolution. How could flowers overcome this “gap”? What would be the most efficient path for evolution to direct flowers toward attracting insect pollinators? By evolving toward something that is objectively there, that can be deduced by any creature with the right organic machinery, regardless of its evolutionary heritage.

Deutsch’s answer to the puzzle is that flowers are objectively beautiful. They evolved toward beauty, developing certain characteristics that express what is objective about beauty, in ways that are hard to fake. Beauty isn’t arbitrary; it’s a signal that’s difficult to generate without actually possessing the underlying properties it advertises. Which is why flowers are attractive to pollinators and to humans (regardless of cultural context; all human cultures find flowers beautiful).

Deutsch extends the argument to art: great art is like a flower; it, too, is “hard to fake.” It contains information about objective beauty that can’t be imitated without also achieving what it achieves (the expression of what is objectively beautiful). If Deutsch is right, this would mean that when humans across cultures and over centuries respond to certain works, they’re not just sharing arbitrary preferences (or even articulating a trail of intersubjective influences), they’re responding to something genuinely there, the way different species of pollinators all detect the attractiveness of a beautiful flower.

Objectively beautiful works of art have escape velocity from their temporal and social contexts (just like the objective beauty of flowers allows them to cross the immense evolutionary gap between species). It’s hard to see what exactly makes a piece of writing objectively beautiful, but we can get a glimpse by looking at what has remained in print over long stretches of time. The sheer number of writers over centuries and across different cultures who appreciate, even love, say, Shakespeare, suggests something objectively beautiful about his work.

A counter-argument is that canonical works survive because of the functions of power, not aesthetics. Shakespeare survives not necessarily because his work is objectively beautiful but because Shakespeare, writing in English, benefited from the power wielded by the English Empire, which made English a global imperial language. From this perspective, forcing students to study Shakespeare is less about aesthetic appreciation than a tool to reinforce power hegemonies (which manifest through culture, and specifically language).

But great pieces of writing don’t just survive time; they survive translation. If beauty were merely intersubjective, beautiful works of art would get stuck in their particular cultural moments and shared assumptions (and many popular and “critical darling” works do get stuck in that way; lauded for decades but fading over centuries), we wouldn’t expect any works to survive translation (and translations of translations over a thousand years) across both time and culture. The fact that some do, and that there’s even a rough consensus about which ones (Homer, Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, the Tale of Genji, the Mahabharata, etc.) suggests these works are tracking something beyond the contingent preferences of their cultural origins.

Dostoevsky is a particularly interesting example because he’s a writer who has uniquely benefited from being widely translated. Many Russian readers find his prose difficult, unpolished, inelegant, sloppy, and verbose, often disliking his style. Vladimir Nabokov intensely disliked Dostoevsky’s prose, calling him a “cheap sensationalist, clumsy and vulgar.” He found his characters and plots melodramatic and unrealistic. Nabokov is not the only one: Ivan Bunin, Turgenev, Henry James, and D.H. Lawrence all disliked Dostoevsky’s writing.

Yet Dostoevsky’s reputation is significant and enduring, especially in America, where it is as strong as ever (sales for both The Brothers Karamazov and Crime and Punishment have tripled since 2020, buoyed by his popularity on BookTok). A big part of this is that Dostoevsky’s prose is improved by translation. The unpolished, clunky, awkward prose can be smoothed over by talented translators, many of whom have transposed his writing into good English style. Something about his work transcends prose style.

Dostoevsky isn’t the only example; it works in the other direction, too, translating out of English. Take Edgar Allan Poe, whose English is often melodramatic, ornate, repetitive, and excessive. The critic Harold Bloom highlighted Poe’s mediocre prose, calling it clumsy, fumbling, filled with “dead metaphors” and “endless self-indulgence.” But like Dostoevsky, Poe’s prose was improved in translation, specifically to French, where translators like Charles Baudelaire elevated his style. Through Baudelaire’s translations, Poe became a “naturalized citizen of the French Republic of Letters,” going on to become a significant influence on the French Symbolist poets6.

The massive influence of writers like Dostoevsky and Poe, despite being somewhat awkward in their original languages, suggests that beauty in writing is located somewhere other than pure prose style; it lies in the structure, the ideas, in the emotional or philosophical depth. Something that survives translation; else why would we still find ourselves captivated by Homer, who wrote almost three-thousand years ago, and whose work has been translated into virtually every language on this planet.

If critics are necessary for mapping the intersubjective web of influences, then time (and translation) help to reveal objective beauty. Something that persists over centuries and across variable cultural contexts.

A counterpoint to the existence of objective beauty in art would be that the art we find beautiful is not consistent. But this needn’t disqualify the existence of an objective standard of beauty. We would not expect all beautiful things to look the same, art or otherwise. Flowers are all “flowers,” but they express the key characteristics of a flower in many different ways. See the range of forms in roses, lilies, orchids, sunflowers, daisies, tulips, peonies, carnations, and lavender.

If objective beauty exists, it has a profound effect on how we create and consume art. For the artist, the idea can be energizing, even illuminating; it would give real weight to the act of creation, providing something tangible (if elusive) to strive towards. But it also raises interesting questions about taste. If beauty is objective, then bad taste would be an error—it would have to be. I think it’s that hangup that keeps many people from taking the leap into the considering objective beauty. It feels intuitively wrong to mark bad taste as a mistake in the same way we can say 2+2=5 is an error. But many things that seem intuitive are in fact an error: it feels intuitive that the sun revolves around the earth, but we now know that is an error—and we overcame this mistake by increasing our knowledge. We may simply lack the knowledge to elucidate the qualities of objective beauty, but we may not remain in that state forever. We may someday require the knowledge to measure beauty.

Right now, we can’t prove that objective beauty exists (or which contemporary works do or do not possess those qualities and in what amounts), but we can treat it as a hypothesis, a mystery worth exploring. The search for something objective, something tangible (even if it’s a phantom), may be exactly the point. There is beauty all around us (in flowers, and in many other things), and the work of the artist might be to uncover that beauty.

To return to Steadwell’s original note about artistic subjectivity, it’s not necessarily that I think he’s wrong, but that if you believe that creativity is subjective, it necessarily determines what you will create. It changes your relation to the act of creation. You will approach it in a Romantic sense: as an expression of your personal self. But if you think of creation as an act of discovery: a way to get at the underlying structure of the world, it changes not only how you create, but what you create.

It’s not unlike Plato’s theory of anamnesis: that learning is really remembering truths the soul already knows. The artist doesn’t bring forth something new but reveals something that has been there the entire time. If beauty is objective, it changes the way art is made. It’s not about invention, about expressing something personal or advancing new forms; it’s an act of discovery.

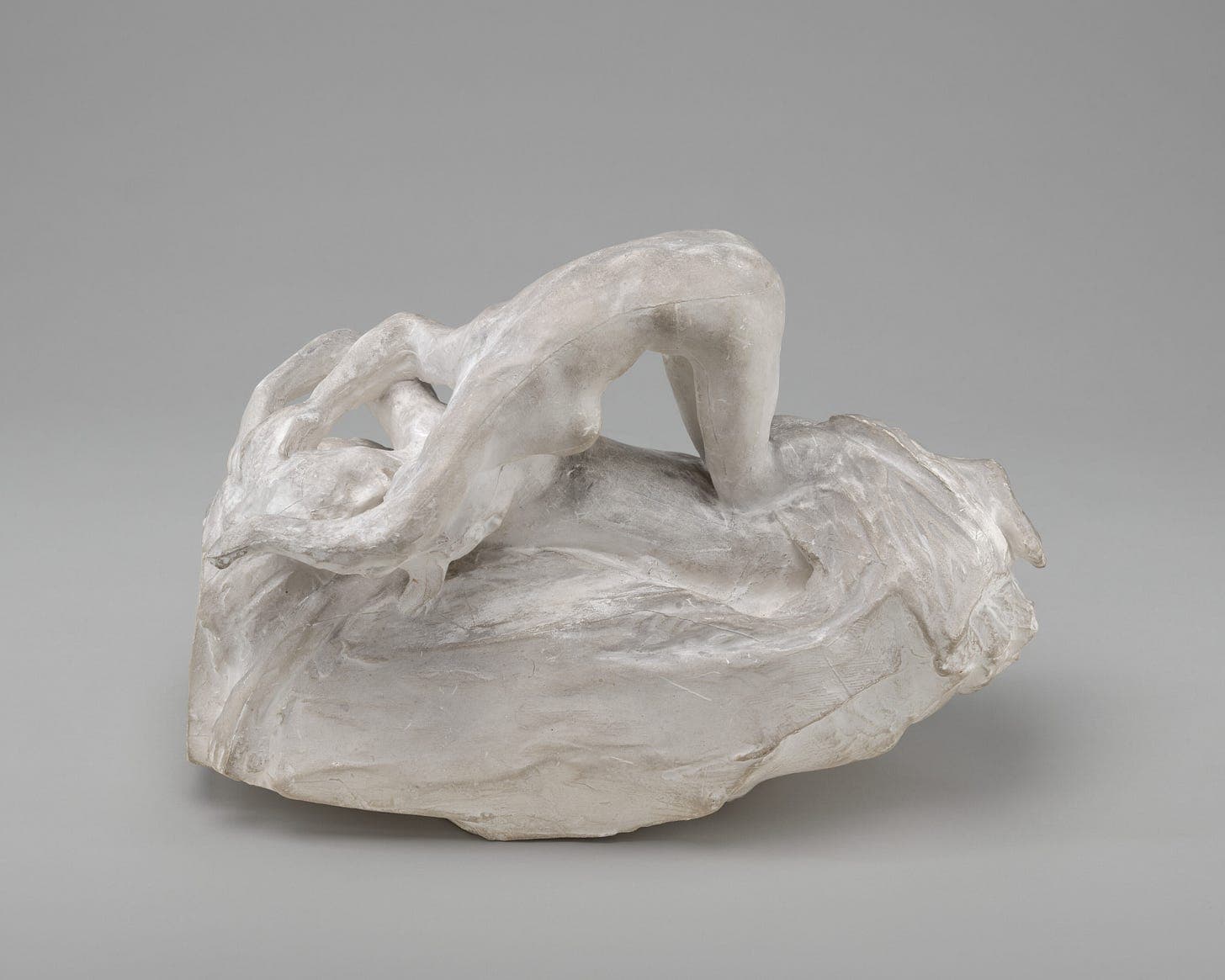

Many artists, from Wes Anderson to Seamus Heaney to Rodin to Mozart to David Lynch to Michelangelo7 have described their creative work as a form of excavation. There is something beautiful that already exists, and the artist’s job is to uncover it.

The Driftless is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Subscribe

For this essay, whenever I refer to “art,” I refer more broadly to creative output in general, not just fine art, but architecture, poetry, novels, music, etc.

The Athenian audience liked Oedipus Rex enough to grant it second place when it premiered. Ironically, the play that defeated it is lost to time; we don’t even know what it was called, only that it was written by the playwright Philocles (none of whose plays survived). Though Philocles’ work was more popular in its time, Sophocles’ plays had greater staying power, especially with critics like Aristotle.

Since cathedrals were considered objectively beautiful when they were built (reflecting God’s divine order), and most people consider cathedrals beautiful today, some architectural enthusiasts propose the idea that cathedrals represent objective beauty, since they have constant staying power. But that’s not entirely true. During the middle period of their existence, after the medieval age and before our modern age, cathedrals went out of style. Many were destroyed in the Renaissance (or left to slowly decay) as aesthetic ideas shifted, and the power of the church waned. It was only in the nineteenth century that they became popular again, largely spearheaded by figures like Victor Hugo, who wrote The Hunchback of Notre Dame specifically to highlight their neglect. His work inspired a national movement for preservation and restoration across France.

His influential paper that put forward this claim is “The Role of Theory in Aesthetics” (1956), which is available to read here.

For reference: “The Mousetrap” (Hamlet), The Sound and the Fury (Macbeth), Infinite Jest (Hamlet), The Black Prince (Hamlet), Something Wicked This Way Comes (Macbeth), Light Thickens (Macbeth), “Out, Out—” (Macbeth), Brave New World (The Tempest), Hag-Seed (The Tempest), “Desdemona: A Play About a Handkerchief” (Othello), The Glimpses of the Moon (Hamlet), Wise Children (As You Like It), The Winter of Our Discontent (Richard III), “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” (Hamlet), Time Out of Joint (Hamlet), On Such a Full Sea (Julius Caesar), Something Rotten (Hamlet), The Way to Dusty Death (Macbeth), The Fault in Our Stars (Julius Caesar), and Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow (Macbeth). And this is by no means an exhaustive list; it goes on and on. But looking at it, what’s interesting is that most of the references come from two plays (Hamlet and Macbeth), and a ton come from a single soliloquy: the “Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow” speech in Macbeth.

Other writers whose reputations arguably increased with translation include Franz Kafka, Thomas Mann, Haruki Murakami, and Karl Ove Knausgaard.

“Every block of stone has a statue inside of it, and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.”